Natraaj, Tallur and the Cosmic Soup

There has been much uproar of late about the exclusion of some of L.N. Tallur’s works from ‘India and the World: A History in Nine Stories’ an exhibition currently going on at the National Museum. Much to the outrage of the arts community, the censorship by the Director General of the National Museum appeared to be on grounds that the depiction of Natraaj was in some way trivialized.

How Tallur and I once crossed paths

Quite possibly before 2014, when he first exhibited at Jack Shainmann in Chelsea, a short walk away from my work at the time. Since I had obligations to fulfill that evening I stepped out at lunch to take a peek at the exhibit which was due to open that evening. Having learnt that there were more of his works being shown at the other location of the gallery a few blocks down, I set out to see if I could make it to the new location before having to head back to work, just when I stumbled into an apparently sleep deprived Tallur who invited me to his opening in a soft spoken polite tone. Even though I was unable to attend that evening, the works I saw stayed with me and upon encountering them once again at the 2014 armory, I had to do a selfie with it, well not quite, as I hadn’t as yet mastered the skill of taking effective selfies, had to ask someone else.

Who is Natraaj

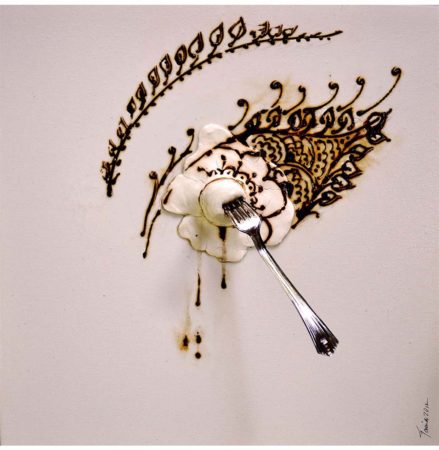

The image of Natraaj or Shiva engaged in the cosmic dance inside a ring of fire atop a dwarf who represents ignorance and epilepsy. The image is that of tolerance above all else as it has a place for ignorance in the midst of the ultimate quest for creation and liberation. As ubiquitous as the original image might be, it has always been open to interpretation as all symbology is. My own take, Algorhythm and Cosmic Dance, veered from the original to a degree.

The idea of the show was jointly conceptualized by the former director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, and Sabyasachi Mukherjee, the director general of the CSMVS was to present the journey of Indian art and culture in a global context by presenting it with collections from the British Museum and other private collectors. In Mr. Mukherjee’s opinion about Tallur’s excluded piece, “It may be a significant art work by the artist but in the context of history and culture, it is against the depiction of Nataraja.”

Instead of adding my own rant to the disappointment on Mr. Mukherjee’s decision on the matter, let me share Fritjof Capra’s observation on the outcome of organized expression of spirituality. The exhibit being the “organized expression” in this case and our stumbling block clearly is the inability to process a symbol for what it is rather than judging it with bias of conditioning.

According to Capra, “Spirituality is a perception of reality in a special state of consciousness and the characteristics of this experience of belonging to a larger whole, connected with everything, are independent of historical and cultural context. But then, spiritual teachers who have this experience are eager to share with others – like the Buddha sitting under the Bodhi tree…

The organized expression of spirituality is religion, which always depends on cultural and historical context. Unfortunately, religion often ossifies and the teachings are expressed as dogma; experience is replaced by faith. You have to believe; you don’t have to experience. These religions, all over the world, also align themselves with politics and very often with right-wing politics.”

The national museum as indeed are all museums, a place of education, that preserves and pioneers a culture much like the cosmic dance of Shiva if you will? The distortion of an inspiration in its organized presentation is almost inevitable. The mark of a progressive institution lies in recognizing ways in which the distortion may be mitigated. with that, I’d like to recall the words of Jiddu Krishnamurti:

“None of the agonies of suppression, nor the brutal discipline of conforming to a pattern has led to truth. To come upon truth the mind must be completely free, without a spot of distortion.”